INTERVIEWERSadly, only the excerpt is available right now. For many others, you can download full PDFs of the interviews.

Isn’t there an enormous temptation as a fiction writer to take scenes out of history, since you do rely on that so much, and fiddle with them just a little bit?

DOCTOROW

Well, it’s nothing new, you know. I myself like the way Shakespeare fiddles with history. And Tolstoy. In this country we tend to be naive about history. We think it’s Newton’s perfect mechanical universe, out there predictably for everyone to see and set their watches by. But it’s more like curved space, and infinitely compressible and expandable time. It’s constant subatomic chaos. When President Reagan says the Nazi S.S. were as much victims as the Jews they murdered—wouldn’t you call that fiddling?

Monday, July 31, 2006

More EL Doctorow

From the Paris Review's endlessly fascinating DNA of Literature feature, an excerpt from EL Doctorow's interview back in 1986.

Sunday, July 30, 2006

Sunday at Borders - 30 July

New and reviewed this week in History and Historical Fiction.

History

Ghost Hunters: William James and the Search for Scientific Proof of Life After Death by Deborah Blum (reviewed by Dennis Drabelle in the Washinton Post) -- Drabelle makes Blum's book sound like just another delve into those wacky Victorians and their crazy sublimation of sex into the supernatural. But medium Euspasia Palladino, who "liked to take off her clothes during her spells and often woke up avid to make love," sounds like she could support a book of her own.

Archie and Amelie: Love and Madness in the Gilded Age by Donna M. Lucey (reviewed by Francine Prose in the Washington Post) -- He was an Astor family scion who escaped from the Bloomingdale Asylum; she was a breathless novelist from a fading Southern family: together, they were a total disaster. Francince Prose makes this turn-of-the-last-century biography sound cheerfully lurid.

The Librettist of Venice: The Remarkable Life of Lorenzo Da Ponte, Mozart's Poet, Casanova's Friend, and Italian Opera's Impresario in America by Rodney Bolt (reviewed by Megan Marshall in the New York Times) -- Da Ponte, a poet who slept his way through eighteenth-century Europe and wrote the libretto for La Nozze di Figaro, sounds interesting enough. But the insanely long subtitle and reviewer's tendency to focus on her own failed book pitches make me much less inclined to read about him.

Historical Fiction

Triangle by Katharine Weber (reviewed by Frances Itali in the Washington Post) -- Itani isn't entirely sure what she thinks of this novel about modern characters with unusual ties to New York's 1911 Triangle Fire, but she knows she loves the first person plural ("We feel we must grieve ..."). The novel could be intreresting, or it could just be a melange of postmodern metafictional techniques -- hard to say.

Brookland by Emily Barton (reviewed by Christopher Benfey in the New York Review of Books [subscription required]) -- The Brooklyn Bridge, designed by John Augustus Roebling, opened in 1883 -- but what if a woman had tried building it seventy years earlier? Barton's novel, which combines fictional letters with narration "reconstructed" from other letters, sounds oddly compelling.

History

Ghost Hunters: William James and the Search for Scientific Proof of Life After Death by Deborah Blum (reviewed by Dennis Drabelle in the Washinton Post) -- Drabelle makes Blum's book sound like just another delve into those wacky Victorians and their crazy sublimation of sex into the supernatural. But medium Euspasia Palladino, who "liked to take off her clothes during her spells and often woke up avid to make love," sounds like she could support a book of her own.

Archie and Amelie: Love and Madness in the Gilded Age by Donna M. Lucey (reviewed by Francine Prose in the Washington Post) -- He was an Astor family scion who escaped from the Bloomingdale Asylum; she was a breathless novelist from a fading Southern family: together, they were a total disaster. Francince Prose makes this turn-of-the-last-century biography sound cheerfully lurid.

The Librettist of Venice: The Remarkable Life of Lorenzo Da Ponte, Mozart's Poet, Casanova's Friend, and Italian Opera's Impresario in America by Rodney Bolt (reviewed by Megan Marshall in the New York Times) -- Da Ponte, a poet who slept his way through eighteenth-century Europe and wrote the libretto for La Nozze di Figaro, sounds interesting enough. But the insanely long subtitle and reviewer's tendency to focus on her own failed book pitches make me much less inclined to read about him.

Historical Fiction

Triangle by Katharine Weber (reviewed by Frances Itali in the Washington Post) -- Itani isn't entirely sure what she thinks of this novel about modern characters with unusual ties to New York's 1911 Triangle Fire, but she knows she loves the first person plural ("We feel we must grieve ..."). The novel could be intreresting, or it could just be a melange of postmodern metafictional techniques -- hard to say.

Brookland by Emily Barton (reviewed by Christopher Benfey in the New York Review of Books [subscription required]) -- The Brooklyn Bridge, designed by John Augustus Roebling, opened in 1883 -- but what if a woman had tried building it seventy years earlier? Barton's novel, which combines fictional letters with narration "reconstructed" from other letters, sounds oddly compelling.

Saturday, July 29, 2006

Raw Data

As part of a larger thing I'm thinking about, I plugged the words "historical fiction" into Amazon. The number one result? Read on... Historical Fiction: Reading Lists for Every Taste.

I suppose it makes sense that a reading list would show up first -- what else is likely to have "historical fiction" in the title? But I still find it interesting that you'd nead a reading list to figure out what historical fiction is out there.

Two other things. One, "Customers who bought this item also bought:"

The Husband by Dean Koontz

Water for Elephants: A Novel, by Sara Gruen

The Hard Way (Jack Reacher Novels), by Lee Child

Read On ... Horror Fiction (Read On Series), by June Michele Pulliam.

And people who viewed this item also bought:

Katherine, by Anya Seton (93% of them!)

A Catch of Consequence, by Diana Norman, and

Sophie's Diary: A Historical Fiction, by Dora Musielak

Follow up on this later.

I suppose it makes sense that a reading list would show up first -- what else is likely to have "historical fiction" in the title? But I still find it interesting that you'd nead a reading list to figure out what historical fiction is out there.

Two other things. One, "Customers who bought this item also bought:"

The Husband by Dean Koontz

Water for Elephants: A Novel, by Sara Gruen

The Hard Way (Jack Reacher Novels), by Lee Child

Read On ... Horror Fiction (Read On Series), by June Michele Pulliam.

And people who viewed this item also bought:

Katherine, by Anya Seton (93% of them!)

A Catch of Consequence, by Diana Norman, and

Sophie's Diary: A Historical Fiction, by Dora Musielak

Follow up on this later.

Friday, July 28, 2006

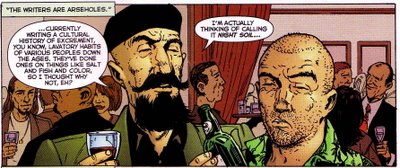

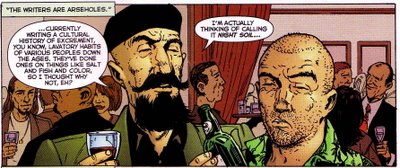

A Complete History of Exactly One Thing

So, a little while back, my fiancee and I started noticing a publishing trendlet in history books. Some authors were taking single, narrow subjects, and using them to tell whole histories. The high-concept certainly isn't new (Daniel Yergin wrote The Prize -- an excellent history of oil -- back in 1993). And some titles sounded intriguing. (Opium, anyone?) But suddenly, the center table at Barnes & Noble seemed filled with titles like Salt, Cod, and Brick.

Turns out, we weren't the only ones to notice.

Garth Ennis, ladies and gentlemen. Not exactly a surgical strike, but you know when he's hit you.

Turns out, we weren't the only ones to notice.

Garth Ennis, ladies and gentlemen. Not exactly a surgical strike, but you know when he's hit you.

First Defeat (1939) by Alberto Méndez

The fiction in this week’s New Yorker, a short story about an officer’s surrender during the Spanish Civil War, has a couple of techniques worth noting.

The (sadly, late) Alberto Méndez tells the story in a first-person plural voice that suggests either a committee trying to reconstruct action, or a team of researchers presenting a paper.

What’s nice is, the point-of-view goes a long way toward developing one of Mendez’s themes, which is the difficulty of knowing what is in someone’s head as they take certain actions.

The narrators rarely use quoted dialogue unless it’s attributable to some other source. The few times they do, they admit they’re speculating. And it’s this admission that hooked me into the story.

The (sadly, late) Alberto Méndez tells the story in a first-person plural voice that suggests either a committee trying to reconstruct action, or a team of researchers presenting a paper.

What’s nice is, the point-of-view goes a long way toward developing one of Mendez’s themes, which is the difficulty of knowing what is in someone’s head as they take certain actions.

The narrators rarely use quoted dialogue unless it’s attributable to some other source. The few times they do, they admit they’re speculating. And it’s this admission that hooked me into the story.

These speculations about our hero’s thoughts are simply our way of explainingThe voice, which is brimming with limitations like these, makes the story feel like actual history. But it also suggests a pair of questions that serve as subtext for the story. What was Alegría really thinking when he surrendered? And, why do these narrators care enough to track down records and witnesses long after the fact?

the events we know to have occurred. We know that Alegría studied law, first in

Madrid, and then in Salamanca. We know from his relatives that he received a

country gentleman’s education in Huérmeces, in the provinces of Burgos, where he

was born, in 1912, to an aristocratic family of old Castilian stock, and reared

in a rambling house with two stone archways and a coat of arms that

distinguished its inhabitants from the local parvenus who owed their fortunes to

famines in the south, where livestock, vines, corn, and olives had succumbed to

anthrax, phylloxera, weevils, oidium, and other curses.

Thursday, July 27, 2006

The Duke of Wellington Misplaces His Horse

Susanna Clarke, who wrote the excellent historical fantasy Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, has an audio version of her new short story (set in the universe of Neil Gaiman's comic fantasy Stardust) up on British Radio 4. Like most of her shorter work (some of which has graced the Op-Ed page of the New York Times), it's a polished little gem, and it has enough real history in it to qualify as more than just "period fantasy." The audio version is only up for a week, although the story will appear in her upcoming collection The Ladies of Grace Adieu and Other Stories.

Assassins!

So, last week, I saw a performance of Stephen Sondheim’s Assassins! at the Signature Theater in Arlingon, Virginia. (Many thanks to lovely fiancée KEL for sacrificing the ticket.) Overall, I enjoyed the show. The music was great, the lyrics were clever, and, despite a few awkward exchanges of dialogue (usually where characters gave each other biographical information, Sorkin-style), it drew laughs and left stunned silences in the right places. But, leaving, I felt a little flat, and I’ve been gnawing at that reaction ever since. Some of it may been a sense of enervation by the actor playing the Balladeer. But I think some of it also has to do with that character in general.

The postmodern conceit of the show – part-revue featuring everyone who’s tried to shoot a US President, part-Pirandello’s “Six Characters in Search of an Author” – kept me interested, enough so that, during the course of the show, I lost track of which assassins had gotten their time in the spotlight and which hadn’t. So I didn’t catch on until close to the end that the sour-faced Balladeer was supposed to be Lee Harvey Oswald. And that’s the big narrative drive of the show. All of these assassinations, from Booth through Hinckley, are just setting up or pointing back to Oswald in the Dallas Book Depository, and Lee’s choice to shoot Kennedy becomes the climax of the show.

Now, I grew up Irish Catholic in Massachusetts, and had parents who came of age during Camelot. I’ve been exposed to the JFK mystique, and I understand that, to a generation, his assassination was a – if not the – pivotal event of their lives. But, from a dramatic standpoint, I wonder if it doesn’t weaken the show. The Balladeer gets a lot of stagetime, but very little development, as if it’s enough for Sondheim that he’s “Lee-Harvey-frikkin-Oswald.”

Only, it’s not. The Balladeer -- especially once it's clear he's Oswald -- comes off as dull, and his role doesn’t quite make sense. He’s a reluctant assassin who nonetheless knows everything important about his predecessors. And, frankly, the other assassins are more interesting than he is. Even Hinckley – whom I think was supposed to come off as bland and vaguely creepy, sitting in the corner in a Barracuda jacket fingering a beat-up guitar – managed to upstage him. He needed more development. His existence was not enough on its own.

So what’s the lesson I’m trying to pull out of this? Maybe that historic importance is not the same as dramatic importance. It can certainly have an effect. But just pointing to something and saying “Look! Historical! Important!” won’t convince the audience on its own.

The postmodern conceit of the show – part-revue featuring everyone who’s tried to shoot a US President, part-Pirandello’s “Six Characters in Search of an Author” – kept me interested, enough so that, during the course of the show, I lost track of which assassins had gotten their time in the spotlight and which hadn’t. So I didn’t catch on until close to the end that the sour-faced Balladeer was supposed to be Lee Harvey Oswald. And that’s the big narrative drive of the show. All of these assassinations, from Booth through Hinckley, are just setting up or pointing back to Oswald in the Dallas Book Depository, and Lee’s choice to shoot Kennedy becomes the climax of the show.

Now, I grew up Irish Catholic in Massachusetts, and had parents who came of age during Camelot. I’ve been exposed to the JFK mystique, and I understand that, to a generation, his assassination was a – if not the – pivotal event of their lives. But, from a dramatic standpoint, I wonder if it doesn’t weaken the show. The Balladeer gets a lot of stagetime, but very little development, as if it’s enough for Sondheim that he’s “Lee-Harvey-frikkin-Oswald.”

Only, it’s not. The Balladeer -- especially once it's clear he's Oswald -- comes off as dull, and his role doesn’t quite make sense. He’s a reluctant assassin who nonetheless knows everything important about his predecessors. And, frankly, the other assassins are more interesting than he is. Even Hinckley – whom I think was supposed to come off as bland and vaguely creepy, sitting in the corner in a Barracuda jacket fingering a beat-up guitar – managed to upstage him. He needed more development. His existence was not enough on its own.

So what’s the lesson I’m trying to pull out of this? Maybe that historic importance is not the same as dramatic importance. It can certainly have an effect. But just pointing to something and saying “Look! Historical! Important!” won’t convince the audience on its own.

This One Only Gets Mentioned for the Title

Article from this weeks' New York Press. Apparently, to some, "Dime Store" means "not my kind of partisan" rather than just "cheap."

And "History" means "Politics." Or maybe "Academics." Or, most likely, "Rhetoric."

I just don't like seeing the (brand new) brand get diluted.

And "History" means "Politics." Or maybe "Academics." Or, most likely, "Rhetoric."

I just don't like seeing the (brand new) brand get diluted.

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

Getting In Their Heads

Novelist Chelsea Quinn Yarbro (who apparently prefers her historical fiction undead-flavored) has an article over on George Mason University's "History News Network" (HNN) on the difference in approach between popular history and historical fiction (besides the obvious "one of them has to get it right"). The article is basically a plug for her new, non-fiction book on the Third Battle of Lepanto, but she still has a few interesting things to say:

The challenge when writing historical fiction is to show the reader not what the people of the time in question did – that is known and readily accessible – but what they thought they were doing. Non-fiction may have a similar goal in mind, but it conveys its understanding of historical events by telling the reader about them. It may seem like a small difference, but it is not.

Notes on Historical Fiction

In the latest issue of the Atlantic Monthly, E.L. Doctorow (of Ragtime fame) has an article – if you can call it that – entitled “Notes on the History of Fiction.” I say “if you can call it that” because he’s really tried to make the title fit. The article is seven quick sketches of different ways in which fiction treats history, using Richard III, War and Peace, and The Iliad (as well as Moby Dick, The Red Badge of Courage, and The Three Musketeers) as examples. His basic point – if there is just one – seems to be that both the fiction-writer (he says “novelist,” but, well, Homer and Shakespeare) and the historian use similar techniques when they write, even though we think we’re reading them differently, expecting the historian to give us verifiable facts, but the novelist “to lie his way to a greater truth than is possible with factual reportage.” So Shakespeare’s So Shakespeare’s “Grand Guignol” (Doctorow's term, not mine) makes Richard III endure, even if the real Richard were probably a better man than one “determin’d to be a villain,” much the same way as the more outrageous stories we tell stick better than dry fact in history. Tolstoy’s selectivity in describing Napoleon in War and Peace slants the portrait toward a tiny megalomaniac, just the same as a partisan historian’s might. And we make a number of allowances for the way Homer tells his story, which we treat as fiction, as some of us do for the Bible, which a different some of us treat as revealed truth.

So, this blog thing, which I had let lie fallow for a while, may get a reboot out of this. I still want to treat it as a research dump (among my many others), but I think this is where I’ll think out loud about those techniques. I like reading history, I like reading fiction, and I get frustrated that they intersect so poorly so often.

But, I have to admit, I’ve never really looked very hard at exactly how they should intersect properly.

Which seems like as good a reason as any to fire this thing back up and see where it will go.

So, this blog thing, which I had let lie fallow for a while, may get a reboot out of this. I still want to treat it as a research dump (among my many others), but I think this is where I’ll think out loud about those techniques. I like reading history, I like reading fiction, and I get frustrated that they intersect so poorly so often.

But, I have to admit, I’ve never really looked very hard at exactly how they should intersect properly.

Which seems like as good a reason as any to fire this thing back up and see where it will go.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)